Nico Vischi

Keywords: Make, Bend, Expand

As an industrial designer, I am fascinated by making as a tool for independence and changing our surroundings, and I’m greatly inspired by what I find around me in my everyday life, especially in the public space. Coming from a big, messy city where different materials and stories are layered upon each other and moving to one where everything is planned out and executed flawlessly was captivating and shocking at the same time. I found myself looking out for the details that escaped this perfection. Why are there certain things that don’t follow the rules? What happens after an object is produced and put out into the real world? What’s the difference between what is drawn and the reality?

These are some of the questions that I’ve asked myself not only during this research but also during my previous education and career as a designer. I believe that design benefits when it incorporates different points of views and expressions, and that it should be available to everyone who wants to improve their life.

Graduation Project

Who makes the city? Why does it look the way it does?

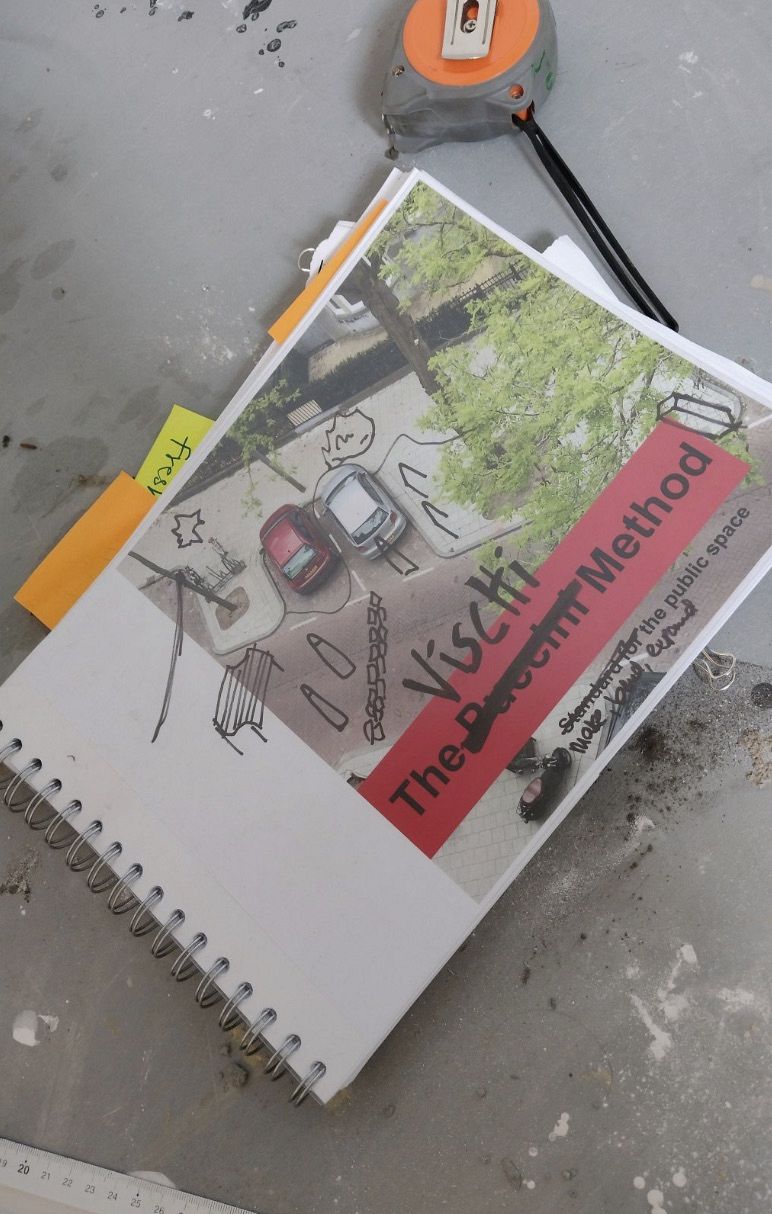

The ‘Puccini Method’ and other manuals for the design of the public space are the reason why Dutch cities look so smooth, clean and perfect. They dictate everything from which kind of furniture can be used to how each brick must be placed in the street. They’re also the reason why some people may feel like they lack freedom, self-expression and control over their public spaces, as these manuals are also telling us, indirectly, how to behave.

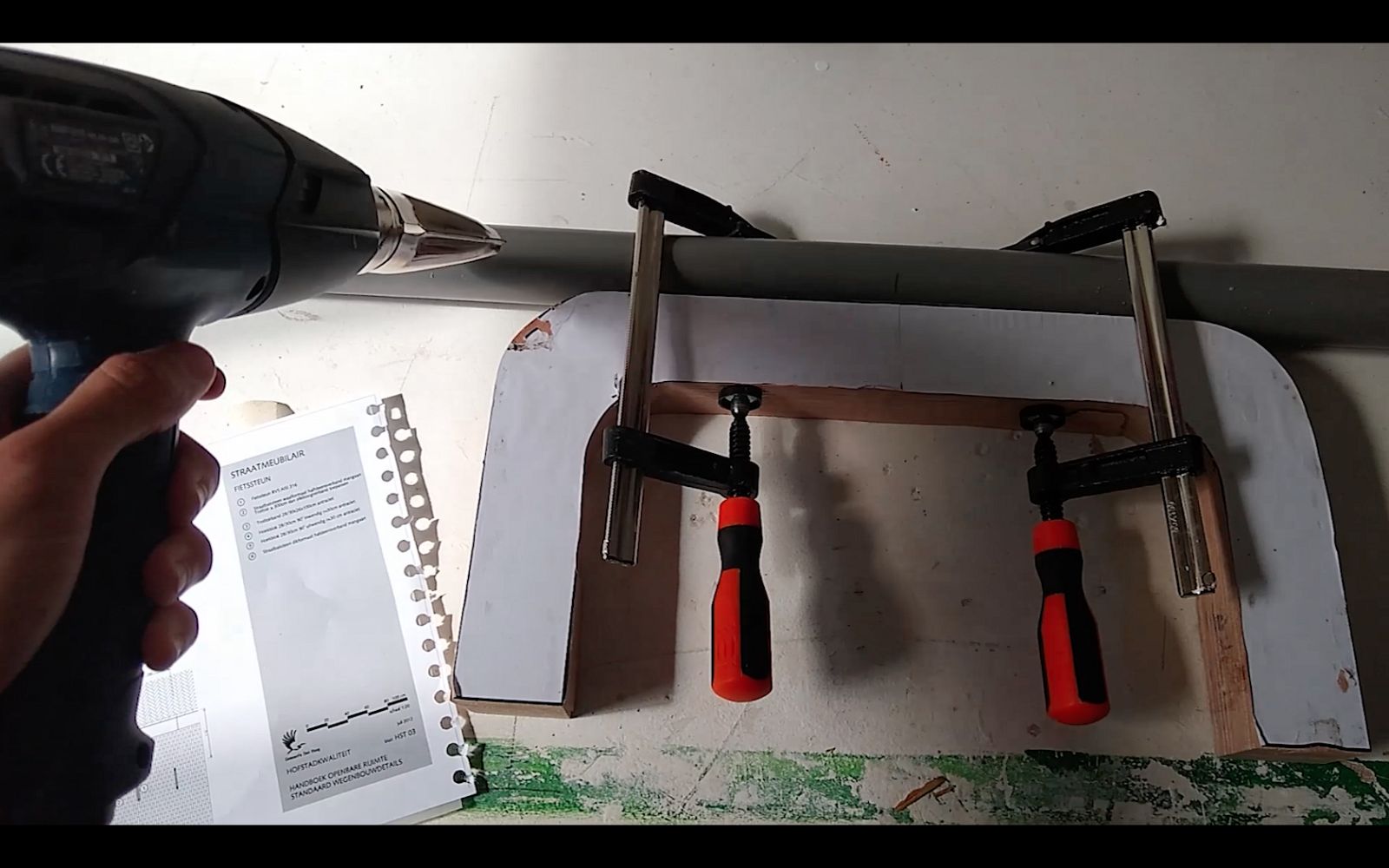

Can we reclaim space for self-expression? By understanding how objects in public space work, how they are made and how they should look, we can make our own rules in the city. The ‘Vischi Method’ consists of quick, handmade objects with which I'm understanding our relationship with the dominant (and sometimes invisible) forms of authority, control and censorship that exist in public space, materialized in industrially designed objects. By sharing my interventions, I want to encourage other citizens to know these rules and manuals so that they can also question them and participate by changing, bending or expanding meanings and limits in the public space.

“Nowadays, it seems to be everywhere – the urban environment that feels smooth, polished and perfect. All buildings seem either new or renovated, and are generally in an excellent condition. Its public spaces are well-designed, well-maintained, clean and safe, if you conform to the rules […] it can be a highly normative, controlling and arguably oppressive environment, in which gradually all opportunities for productive friction, sudden transitions or subversive transgressions have been eliminated. Here, it’s almost impossible to leave one’s own traces, or intervene according to one’s own ideas and desires. […] However, some modest forms of opposition could emerge from the notion of ‘porosity’, or the idea that it might be possible to create, organize or design cracks in the smooth surface of the city.”

René Boer – ‘Smooth City is the New Urban’, in: Archis Magazine, Volume 52, 2017