Scattered throughout the Bleijenburg building and hidden in plain sight, The Burrow is an installation that seeks to pull the rug out from under our feet through laughter. In laughter we encounter the limits of the world and of what we think we know as real. As Georges Bataille writes: “We laugh, in short, in passing very abruptly, all of a sudden, from a world in which everything is firmly qualified, in which everything is given as stable within a generally stable order, into a world in which our assurance is overwhelmed, in which we perceive that this assurance was deceptive.”

Perhaps for a brief moment, within the excess of the laughable and in the absence of the known, we might find ourselves encountering thought itself.

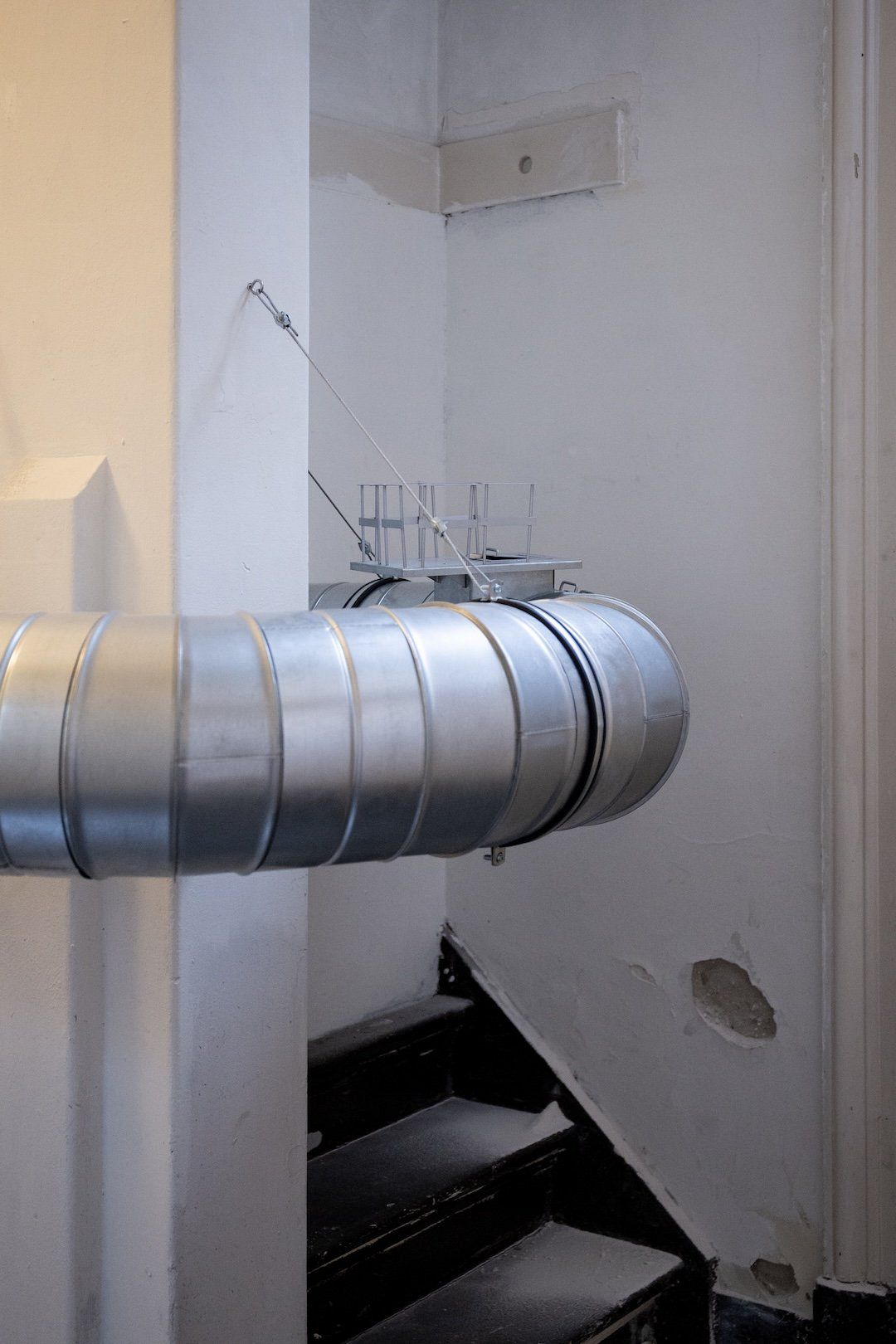

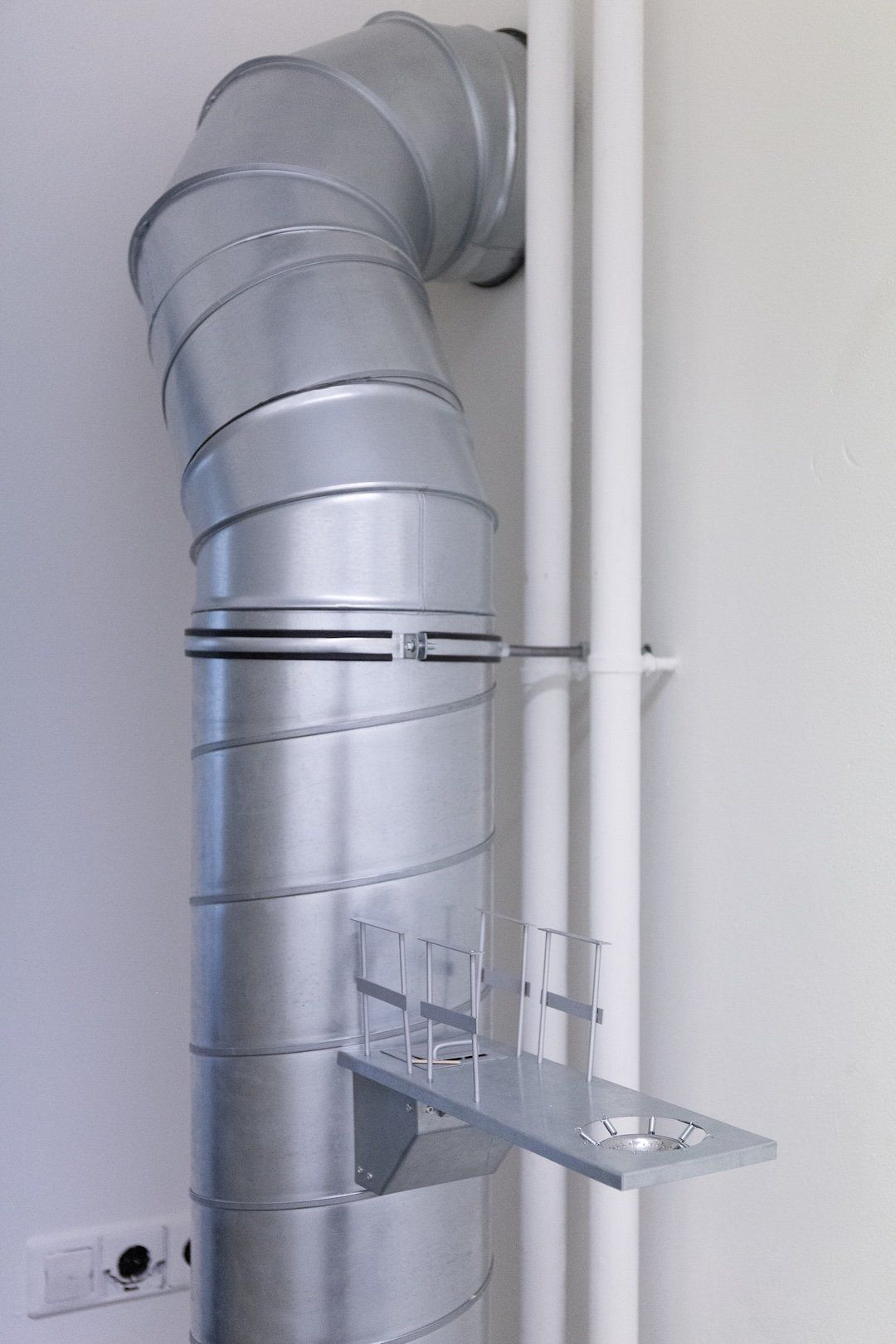

Here, come closer. Do you smell that? It smells like the time it's taken for the air to go stale. Not even the doorstoppers, strategically placed to allow air circulation, manage to get rid of the damned musty smell that bathes this space in gloom.

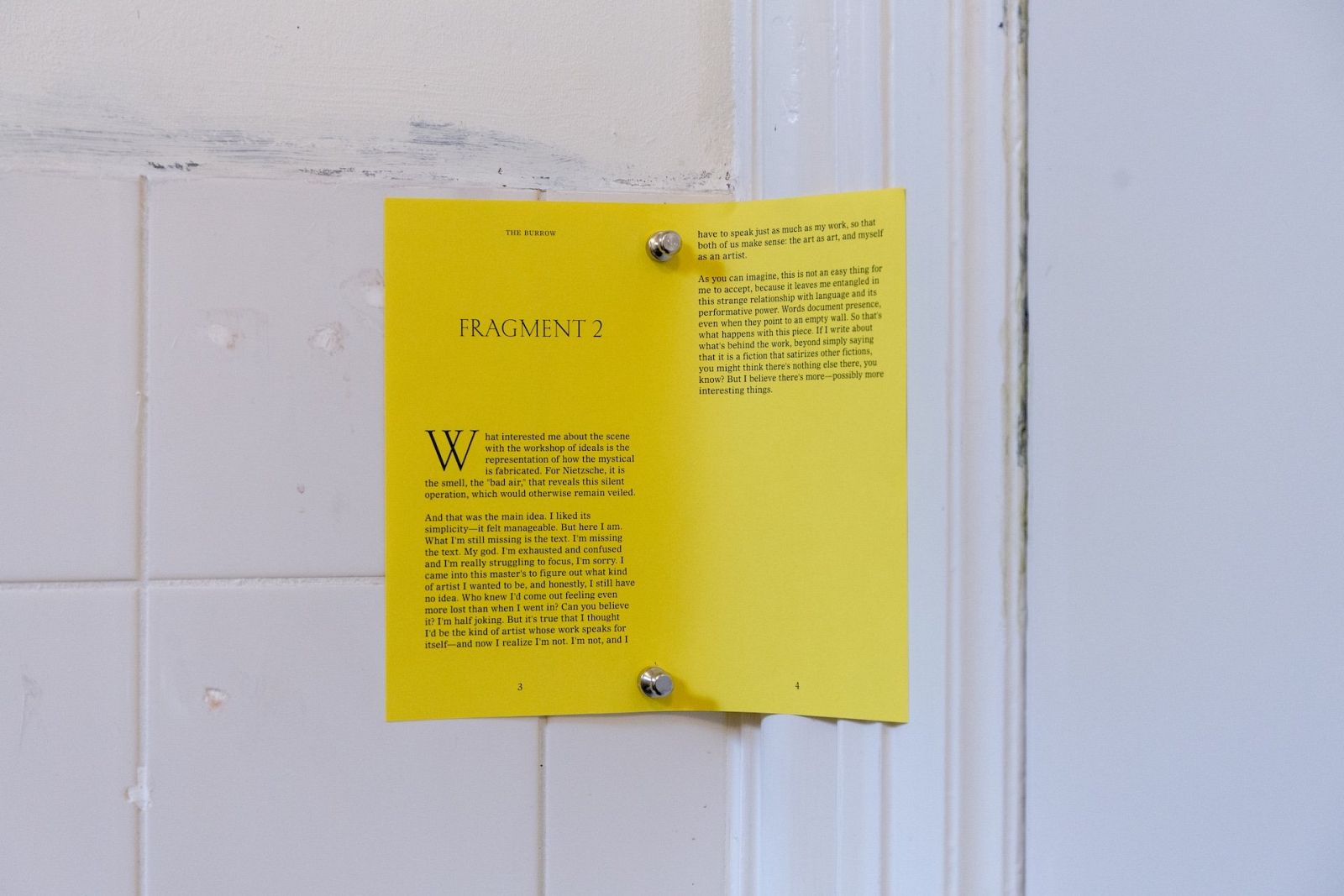

What you're smelling is the foul air Nietzsche points to in the fourteenth chapter of On the Genealogy of Morality. "But enough! enough!" he writes. "I can't bear it any longer. Bad air! Bad air! This workshop where ideals are fabricated—it seems to me just to stink of lies."

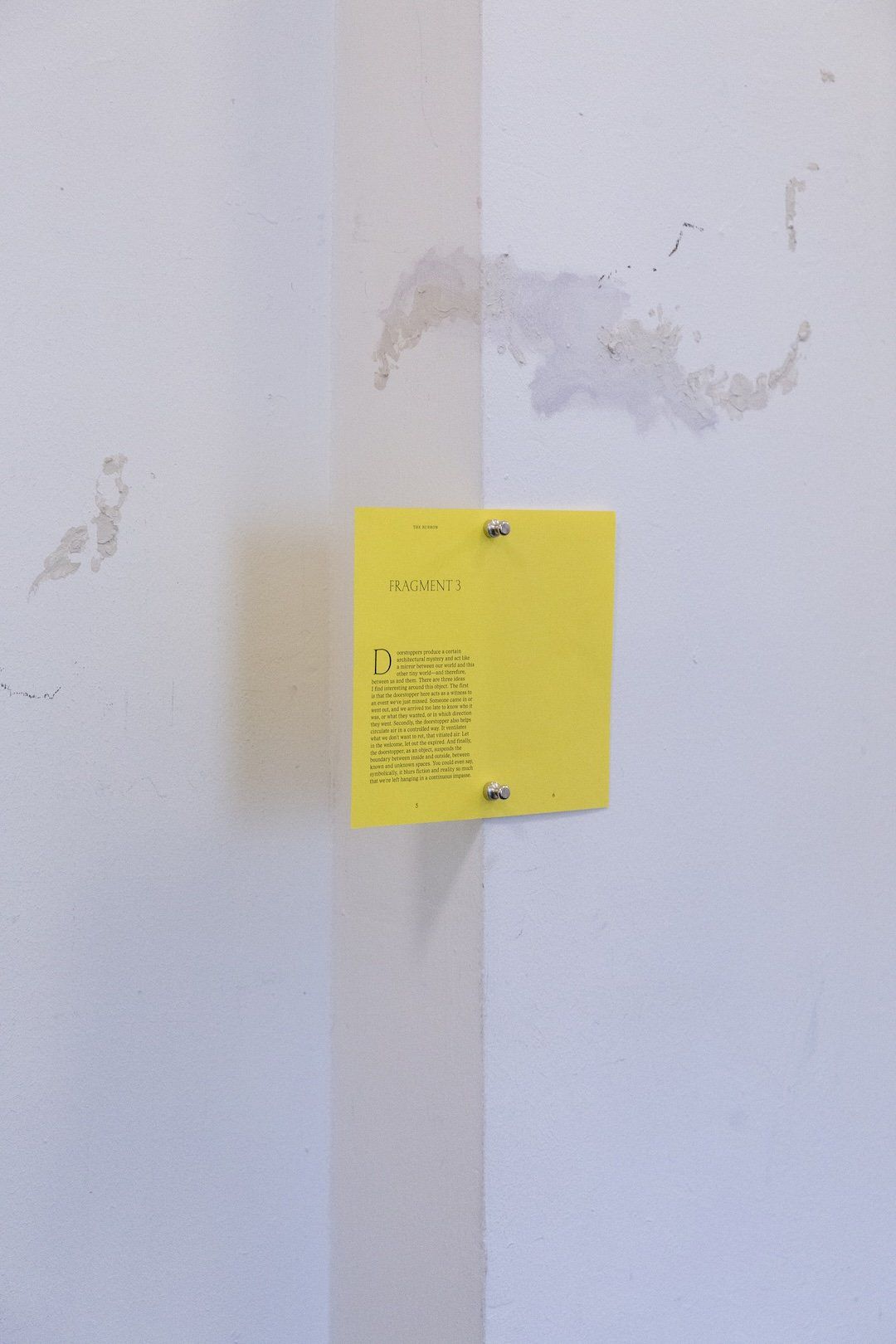

In it, Nietzsche satirizes the machinery of transcendence that elevates moral ideals above the human, cloaking them in an air of mystique. Where the father says, "this is so because I say so," these ideals, always distant and mysterious, are founded on a legal opacity that must be accepted. For Nietzsche, it is smell that reveals this mystical operation that would otherwise remain veiled.

The question of the mystical becomes pressing when we arrive at the following crossroads: On one hand, we have been socialized into a world that assumes our blind obedience to law and its systems of authority. The idea that law is a fiction constructed to organize life is not new, yet our relation to law, as Agamben points out, relies mainly on an act of faith. On the other hand, we live in times where the fiction of law has shattered before our incredulous eyes. As Rita Segato notes, the message behind the genocide in Gaza is the end of global law. "There is no law," she explains. "It is a declaration that the power of death is the law."

In this situation, both our faith and our agency are short-circuited, leaving us at the mercy of despair. It is here that I wonder if there are other ways of relating to the world and its fictions. How do we reflect on the nature of our own belief systems—humanly constructed and yet so deeply soaked in mystique and unavailability? How do we reimagine belief itself?