What is it like to be you? That is quite a big question, right?

For those diagnosed with autism later in life, that question becomes more than abstract—it becomes personal. It often means rethinking your sense of self, and then trying to share that shift with others. But instead of being met with understanding, you’re often asked a different version of the same question: What is it like to have autism?

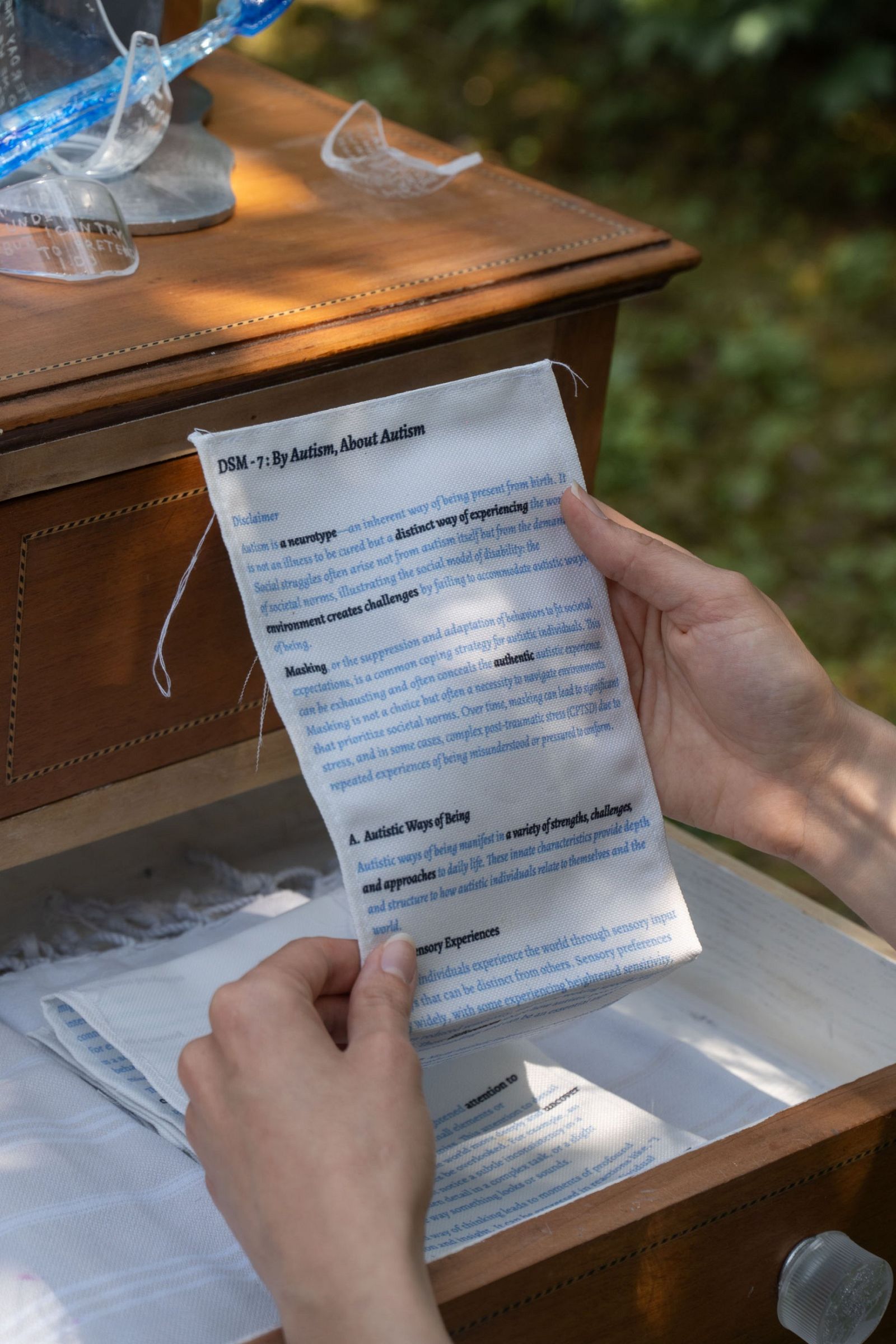

At its core, this project is about voice—about giving autistic people, including myself, space to rediscover and express our own. Autism is not a deficit; it’s a way of being. But many of us feel disabled by environments that aren’t designed for us. Clinical definitions still describe autism from the outside—how we look, not how we feel. And while we’re often labeled as poor communicators, maybe we just communicate differently.

This project is designed around that idea. At its center is a cabinet of curiosities—an everyday space where many of us get ready to face the world, put on a mask, and practice conversations. Inside, you’ll find trinkets that serve as conversation starters, such as a mask made from pills, which sparks discussion about the medical model of disability. There’s also a workshop space in the back. During the workshop the participants will play a card game, built on images, poems, and terms that invite associative, intuitive dialogue—another way of speaking that aligns with autistic communication styles. During the show, small group activations will bring these tools to life (These workshops will take place 2 times a day, at 13:00 - 13:45 and at 15:00 - 15:45).

So, each element of this cabinet invites a small, zoomed-in exchange. Together, these details form a more nuanced and human understanding of what it can mean to be autistic. Because sometimes, the story really is in the details.

In this workshop, participants use hand-drawn playing cards to respond to poems, objects, and theoretical terms. Rather than starting with words, they first choose an image that resonates. Through these metaphors, they share how they relate—using a more associative, visual way of communicating that often feels more natural to autistic people.