Leonie Harkes

Keywords: Appropriation, Postproduction, Memento mori

In today’s Western capitalistic society, our fixation on happiness can seem almost religious. Happiness, comfort and pleasure are the closest things we have to a summum bonum, the highest good from which all other goods flow. This obsession has trickled down into our visual culture. Take social media content, which generally provides an illusionary visual representation of reality, predominantly skewed towards the joyful, beautiful and enviable: ‘What appears is good; what is good appears’. Even though pain, sadness and death are an inevitable part of every human life, even the most fortunate, unhappiness becomes the summum malum, the greatest evil to be avoided. Which results in a tendency to hide or suppress the manifestations of sorrow, let alone visually represent them. In contrast to 17th century Dutch art, when ‘memento mori’ artworks were specifically designed to remind the viewer of their mortality and of the shortness and fragility of human life. With my wallpaper “What Goes Up, Must Come Down” I’m trying to subtly reintroduce the concept of ‘memento mori’ into the 21st century. Bringing together appropriation, postproduction, psychology, silk screen printing techniques and a common household product. Not hiding, denying or suppressing the painful side of life, but accepting pain as an inevitable consequence of being alive and creating space for it. For whomever might need that space. It may not shake the foundations of the current order, but at least it allows sorrow to be present against the backdrop - and that is a start.

Thesis

Unoriginal Genius¹ - The Truth of Art²

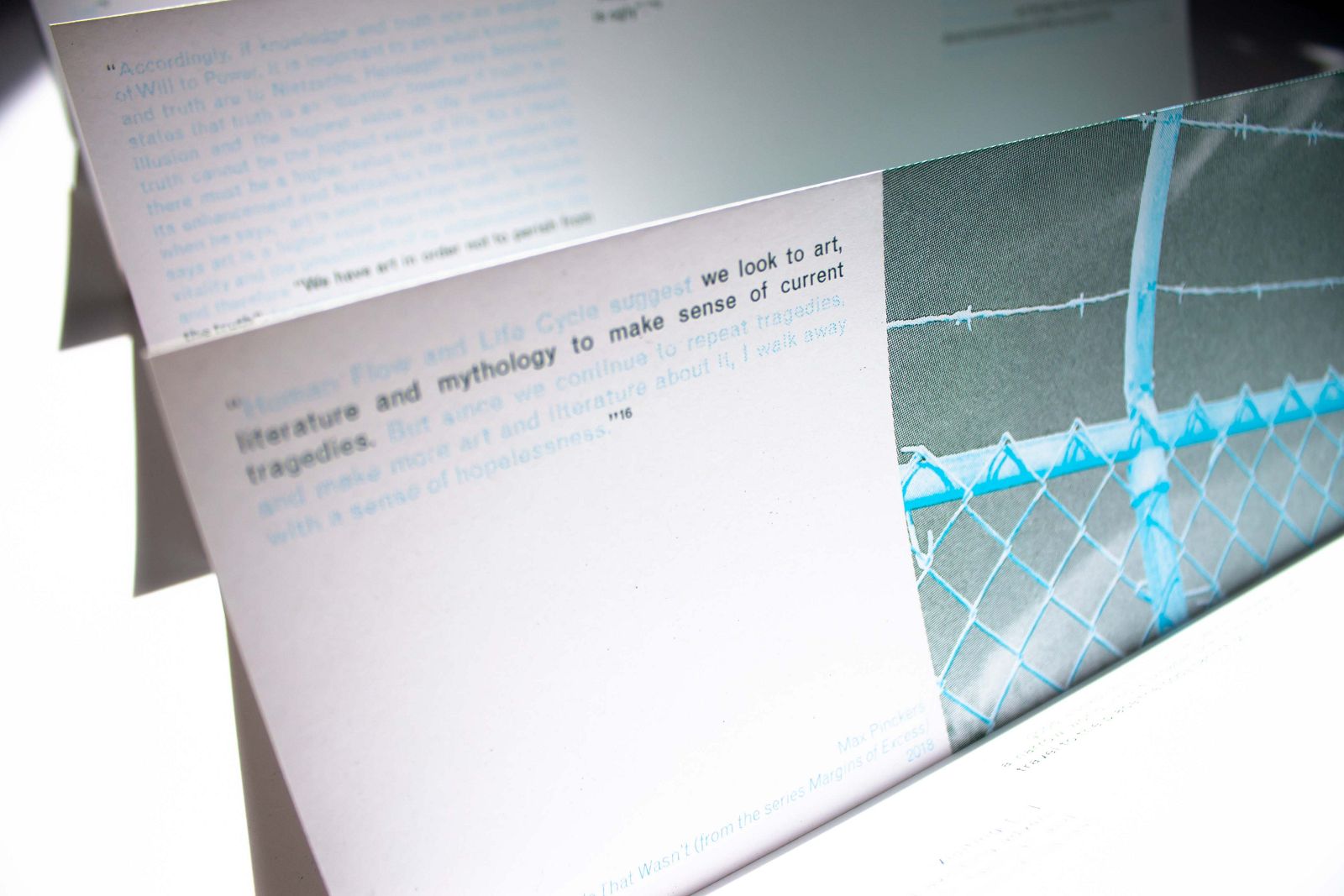

In today’s post-millennial and so-called “post-truth” age, the boundary between reality and fiction seems increasingly hard to distinguish. As a result, there is an impression of a world of extreme relativism, where everybody lives in their own version of reality. In light of the current problematization of truth, factuality, and objectivity: what role should art play? Creative practitioners have often adopted an anti-fact stance yet, in this thesis, light is shed on different attitudes to facticity that have emerged in response to our times. One of the main goals of engaged art is to unveil non or less visible truths about pre-existing, hegemonic narratives. This provides us with a standard by which social critique can operate: the critic is not the one who debunks, but the one who assembles by means of representation. A stance which is evident in documentary practice and postproduction with its strategies of mixing and combining. A way of thinking of a better, more beautiful world that manifests itself in the liminal zone between fiction and non-fiction, imagination and reality, utopianism and realism. In the aesthetic of the real, fiction can become reality and reality is constructed through speculation in the shadows of human imaginations.