Tina Farifteh

Keywords: Europe, Fear, Refugees

Tina Farifteh is a Dutch-Iranian artist based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She obtained master’s degrees in Economics and a bachelor’s degree in Arts. Thanks to this academic and cultural background, she is used to seeing the world from different angles.

She is a visual researcher whose work lies at the intersection between arts, politics and philosophy. Her interest lies in human nature and the politicization of ‘life’ – particularly, the administration and control of life. She is inspired by the work of philosophers Agamben, Foucault and Arendt. Specifically their concepts of ‘bare life’ and ‘biopolitics’.

In her work, she reflects on the impact of man-made power structures such as nation states and corporations on the lives of ordinary people. Often focusing on people stuck between the ‘natural’ life and the ‘conventional’ life. People not only excluded from the privileges granted by the ruling political and economic systems, but often damaged by these to make the system ‘work’.

Her photographic approach is research-based and conceptual. Often combining images, text and data. The goal is to seduce us to look at topics that we prefer to look away from because of their complexity or discomfort.

In her earlier project Killer Skies (2018), she explored the impact of the ‘dronisation’ of armies. Currently she is researching and reflecting on the situation of refugees on the move or stuck at European borders. This work focuses on borders, bodies, camps and the political language used to normalize the absurdity of how we are currently dealing with these topics.

Graduation Project

I was born in Tehran (Iran). I came to the Netherlands when I was 13. The only thing I knew about the Netherlands was that it was below sea level. I had heard the story of the boy who put his finger in the dike and saved the country from flooding. The decision to move to Holland didn’t sound like a wise idea to me. Why move to a country that could be flooded at any moment?

During my 25 years here, the political climate has shifted. The public debate on migration has become harsher, heated and polarized. What would have been considered right-wing xenophobia back then, is now considered mainstream. Populists simplify complex realities into good and evil, victims and perpetrators: ‘us’ versus ‘them’. Their rhetoric often consists of dehumanizing words and metaphors. One of these is ‘water’.

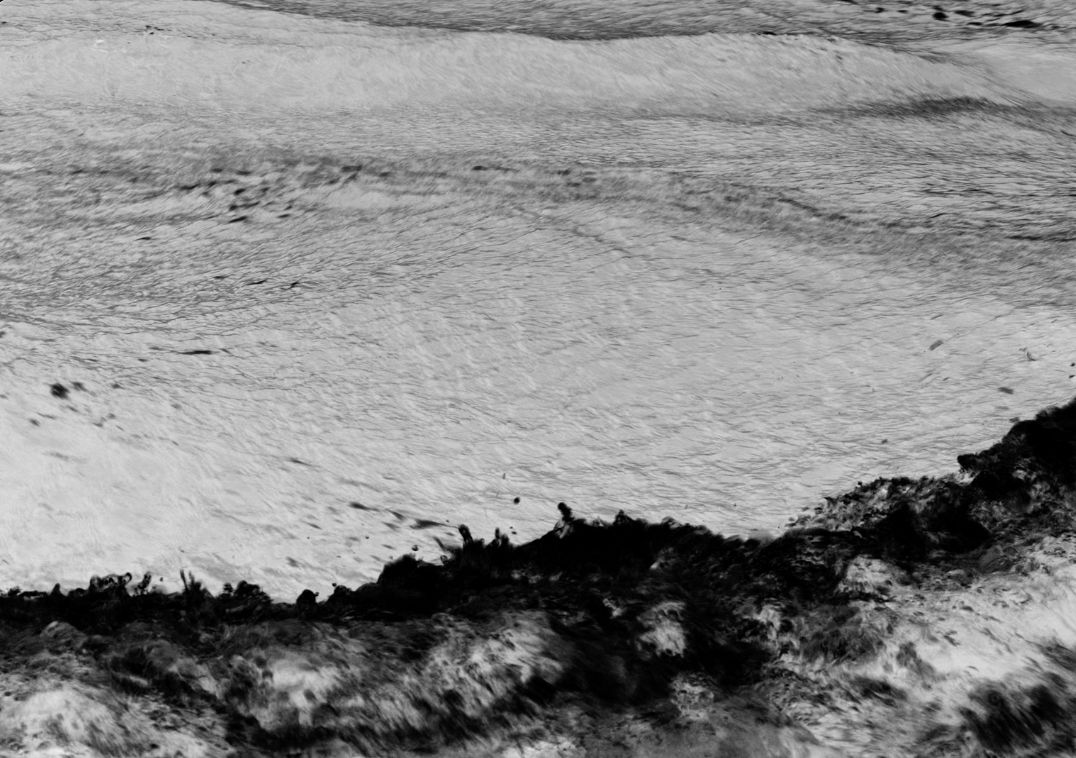

We are inundated with headlines on how migrants are streaming into Europe, flooding the continent, bursting through national borders, threatening to submerge our culture and destroy everything we hold dear. Their rhetoric is gradually being adopted by mainstream politicians and media. It seeps into laws and policies and leads to direct action. Words are the first step in legitimizing walls and violence.

In reality, water is not an immediate threat to the average Dutch person; but it is a huge threat to the thousands trying to reach the Netherlands. People trying to survive the Mediterranean Sea in rubber boats. Trying to survive winter on the Aegean coast in primitive tents. To them, water really is deadly.

In this project I aim to dissect the water metaphor, to understand and visualize the dominant discourse on migration and question the current framing of refugees as a natural disaster.

Who is afraid?

Who is really threatened?

What is the price of fear?

Who pays this price?

Tina Farifteh

The Flood (2021). Audiovisual installation, 9’27”.

Concept, research, video: Tina Farifteh

Sound design: Tijmen Bergman

Video engineering: Daan Hazendonk

Special thanks to Geert Ates and UNITED for Intercultural Action. For their endless efforts to collect data and to publish the annual list of refugees who have died on the way to Europe since 1993.

⚠️ Warning: the content of this installation may trigger shock or trauma, particularly in people who have fled by sea or who have worked with boat refugees. ⚠️

EMPATHY, THE IMAGE AND ME

Thesis

Prompted by her intense personal response to the news of the devastating fire at the Moria refugee camp on Lesbos in September 2020, in this thesis visual artist Tina Farifteh asks the question, what is empathy? And, more importantly, what is it good for? How does our response to images of suffering and devastation affect our attitudes and our ability to act?

Taking a deep dive into the evolution and science of empathy as a phenomenon, a human response and a purported beacon of hope in a suffering world, she examines the role of empathy, in particular in relation to “making the world a better place”, identifying the different types of empathy we humans can experience and what these can lead to. As Europe and the world continue to struggle with multiple humanitarian crises, exemplified by the ‘refugee crisis’ and how it is reported, Farifteh wonders whether empathy is indeed the panacea it is often held up to be, uncovering in the process some darker sides to this usually universally applauded human trait.

She then investigates the role of the image as a catalyst for human responses and actions. What images push our empathy buttons, and what types of empathy do they evoke? How is this done, why, and with what results? How can it be done better, smarter or more honestly? Having investigated how images and empathy relate to one another in our image-saturated culture, she concludes that: “We are both empathic and hateful. The world is ugly and beautiful. As Arthur Jafa said, ‘It’s not all good, it’s not all bad.’”

Empathy is a precious resource, but it is not perfect. Farifteh believes that despite its shortcomings, it is indispensable. “Empathy could be the trigger. The spark. The start. To pay attention, to look, to see the pain, to recognize injustice, and to care.”

But in order to do ‘good’, Farifteh argues, we need to step back, think and make sure we don’t fall into empathy traps. As Paul Bloom said, “rather than relying fully and solely on empathy to make the world a better place, we need to deal with complex issues and be mindful of exploitation from competing, sometimes malicious and greedy, interests”. In order to do good, we have to use empathy with intelligence and creativity. But also with teamwork.

Finally, she argues that rather than attempting to use the image to impose a desired response on the viewer – whether empathy or something else – the image-maker can better strive through their images to “add to the conversation.” After all, in a time of polarisation, social media bubbles and echo chambers, an ‘empathy deficit’ and rising political populism, an open, honest conversation taking into account the full scope of our human nature is arguably now more urgently needed than ever.